文|侯鵬暉(日本大學藝術學研究科藝術專攻博士)

1946年出生於彰化縣二林鎮八間客家庄的葉裁,擁有相當獨特的攝影人生經歷,是一位拍攝許多台灣珍貴鄉土紀實影像的攝影家。

初遇攝影啟蒙──鄭桑溪老師

葉裁年輕時接觸攝影的經驗中,與台灣攝影家鄭桑溪老師相識,是他一生中難以忘懷的鼓舞啟蒙。葉裁除了受到鄭老師許多攝影方面的專業指導與提攜,也在老師家中閱讀到許多攝影相關的專業書籍,大大擴展了葉裁對於攝影藝術表現的想像。

台灣攝影教育研究者吳嘉寶,曾經評價鄭桑溪為台灣攝影史當中,介於第一代攝影家(曾在日本或中國學習過攝影知識,如張才、李鳴鵰、鄧南光等)及第二代攝影家(以1970年代的「V-10視覺藝術群」為代表)中間的攝影家(注1)。

相較於之前世代多為走向攝影沙龍式的畫面優美及畫意佈局的特性,鄭桑溪的影像風格在保有紀實的基調當中,也強調出畫面當中不同元素之間的視覺呼應關係。鄭桑溪不迎向主流較為刻意的沙龍美感,而是以在人們生活當中所捕捉到的自然神情與生活狀態的紀錄作為攝影時的重點,這點從葉裁1960到1970年代裡大量拍攝新竹一帶的人文風景影像裡,也能感覺出他深受到同時期鄭桑溪攝影概念的影響。

而鄭桑溪對於攝影藝術的知識見地,不僅止於自身的創作表現,也積極提攜了許多攝影後輩,在當時的台灣攝影發展有著舉足輕重的定位。而葉裁在這段時期跟鄭老師學習攝影的際遇,也對他未來的攝影之路奠定了重要的基礎方向。

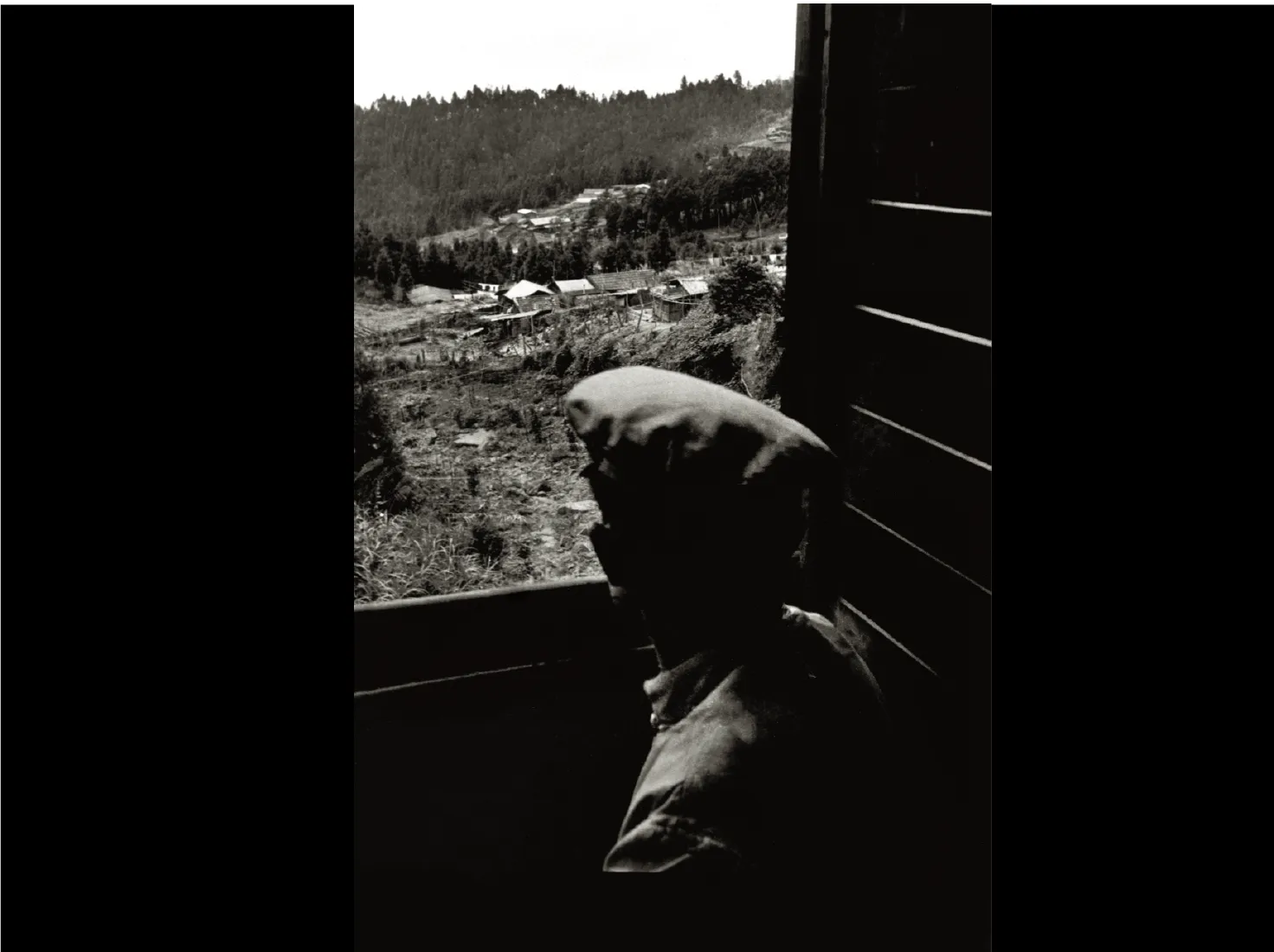

〈車仔卡輪無結無煞〉,新竹五峰,1966,葉裁攝。

〈著靚衫分人請生日〉,新竹北埔,1966,葉裁攝。

國際攝影工作交流經驗與其影響

葉裁在1975年成為了伊士曼公司的特約攝影師,在海外執行拍攝「有超過100年以上歷史古蹟的國家」的工作。在這段時期葉裁磨練出許多拍攝的實務經驗,也見識到各國多樣的城市人文景觀。

不僅如此,在國外工作期間,葉裁參加過許多世界各國知名攝影家的工作坊,包括發明分區曝光系統(zone system)的黑白攝影名家安瑟・亞當斯(Ansel Adams, 1909-1984)、長期拍攝北海道美瑛與富良野的風景攝影家前田真三(Shinzo Maeda, 1922-1998),以及出版《決定性的瞬間(The Decisive Moment)》而牽動世界攝影走向的亨利·卡蒂爾-布列松(Henri Cartier–Bresson, 1908–2004)。葉裁與這些知名攝影家曾有過珍貴的交流經驗(注2),不論在技術上與攝影觀的見聞歷練,在同時期的台灣攝影家當中,可以說是相當難得而獨特。

這段時期豐厚的經驗累積,讓葉裁之後能夠更加篤定而穩健地走在攝影的路上,例如至今仍鍾情於暗房並堅持親自製作黑白照片細節表現的職人精神,或是藉由長期密集拍攝特定地區追求獲得更為豐富極致的風景面貌,以及注重畫面當中的視覺要素彼此間能達成協調與秩序感的街頭抓拍等,都分別與前述的知名攝影家們有著部分相似之處,而葉裁又進一步將這些特性融合成就了獨自的攝影作風。

〈生命河壩頭前溪〉,新竹竹東,1995-2000,葉裁攝。

〈打極樂仔〉,桃園龍潭,1983,葉裁攝。

結束伊士曼公司的工作,1984年返台結婚後葉裁選擇定居新竹峨眉,此時期台灣攝影表現也更朝向了重視鄉土及報導攝影的方向,但對他而言,或許更接近回歸初衷的心情,而非受到外界攝影潮流變化的影響,繼續深化拍攝桃竹苗鄉村影像,始終堅持走在自己的攝影道路上。他透過長期拍攝,在影像的質與量都與一般攝影者有明顯的不同。台灣的攝影發展史裡,還有許多尚待深入發掘之影像,或是以現代視點轉譯詮釋的可能性,亦是此書出版格外具有意義的部分。

在需要長期進行頻繁移動的攝影創作,往往都會比拍攝家鄉或在地還要困難上許多。葉裁長期拍攝北埔一帶鄉村風景,最初或許是從兒時記憶的印象開始,而移住異地後的長期拍攝,逐漸轉換成一種自身關注且不可取代的影像現實體驗,這並非是一般程度的動機或單純毅力就能輕易達成的。

此外,葉裁至今為止都在自家房間改造的暗房製作照片,在約2-3坪的空間裡,有部分自行加工改造的放大機、恰好能擺放顯像盆的狹長作業平臺,以及小床鋪與布衣櫃等,成為一種暗房作業與極簡居住生活感所融合的空間,長年於此進行暗房放相的生活,應該是一般攝影者難以想像的。可以明顯感受到葉裁終身與攝影為伴的實踐精神,即使是在極限的環境裡,心境仍然自在而不受拘束。

影像視覺式的攝影集編排

葉裁以抓拍為主的攝影風格,畫面飽滿而富含故事性,單張照片可詮釋的內容相當豐富。影像沒有過於誇飾的視角,平實當中顯現出濃厚的庶民生活感,在鄉村風景、祭典活動、人事物的影像捕捉之間取得平衡,影像裡也有著新竹、北埔等客家地區特性。而此次並非以圖錄或是編年的方式編輯,而是將「攝影書」當作一個獨立的作品,將多數影像以現代編輯手法重新構成為一段大時代的影像敘事。

此攝影集收錄的影像,以葉裁出國前(包含部分短暫返台時拍攝的內容)以及返台後作為分水嶺,大約剛好各佔一半。當中約有4成是介於1960至1970年代的影像,使本書營造出一股不同於現代感受的懷舊基調。本書在巨觀上能隱約感覺到時間的流動,在微觀時卻非依照絕對的時間序列編排,而是更著重在以視覺影像的脈絡關聯,讓穿梭於現今過往之間觀看影像群的經驗,能夠感受到一個更為融合的整體,這是本書在處理歷史影像時的獨特呈現。

本書從雲霧瀰漫的山間景色開始,接著進入到山村裡,顯露時而辛勤割稻、時而休憩談笑的純樸鄉村生活風貌,當中穿插著坑窯、炭坑、看戲、擺地攤等當地特有風光與過往生活習俗,或是搶孤、燒王船、媽祖等民俗信仰活動,以及原住民歲時祭儀的場面,豐富的影像更對接著台灣各種族群的民間生活意象。影像裡也有水底橋與鐵軌等連接外地的交通幹道,不僅是遠觀式的拍攝,也捕捉了人們在這樣環境裡生活的軌跡,透過遠近距離的人、物、景之間交替切換,營造出緩慢的時間流動感。偶爾穿越時空,跳接到現代野台戲戲棚下孩童的神情,也似乎能將過往現今累積的情緒氛圍串連在一起。

〈做中元〉,新竹芎林,2016,葉裁攝。

〈矮靈祭〉,新竹五峰,1986,葉裁攝。

〈坐等看表演〉,新竹竹東,1969,葉裁攝。

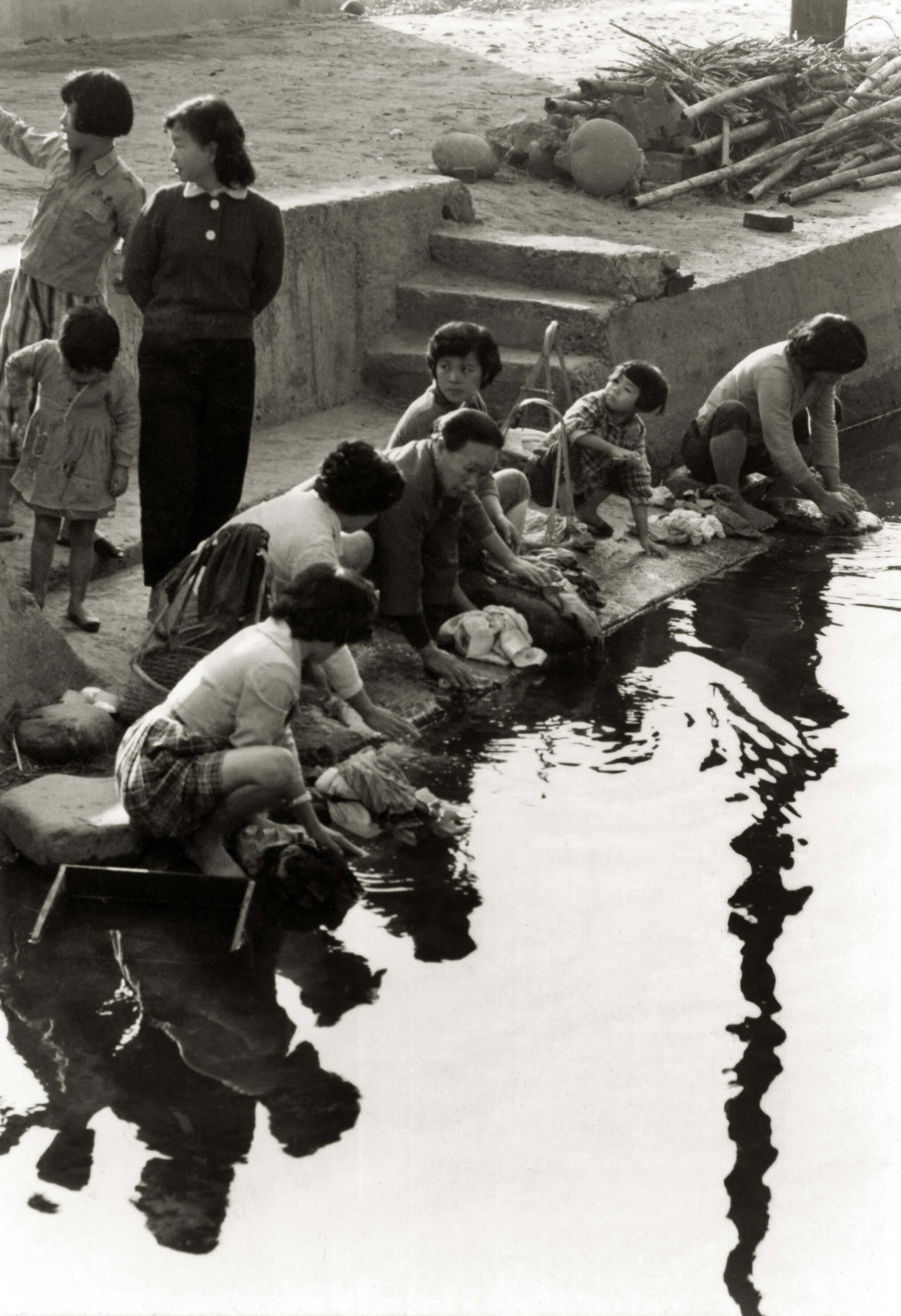

在眾多種類與時空交錯的影像當中,「水的意象」是一個重要視覺,除了河川溪流及海岸線風景地貌,還有洗衫坑、抓蝦、撿漂流木、堤防上的人等,充分展現許多與水共居的庶民生活樣態。本書最後一張的峨眉溪影像,前景的寬敞河道延伸至遠處山景,既壯闊也同時保有細膩的表現,讓書中豐富的川水脈動意象,能夠有所呼應貫穿到最後,凝聚匯集而繼續流向遠方。

〈洗衫坑〉,新竹竹東,1966,葉裁攝。

〈捉蝦公毛蟹〉,新竹橫山,1965,葉裁攝。

〈牛軛湖〉,新竹峨眉,2003,葉裁攝。

《光景》就在鄉村影像中不斷深入探尋,又在時代間反覆轉換,將傳統的影像透過現代的編輯手法轉化,賦予了另一種重新認識與體會葉裁影像魅力的可能性。

葉裁始終專注於自己追求的創作世界,長期拍攝所包含的時間跨度,以及其中顯現出的民間生活狀況轉變,都確實留存於他的影像作品裡。不論是作為個人藝術表現的實踐,或是記錄台灣歷史發展的層面上,都可以說是極具意義。

葉裁的影像也讓台灣攝影發展裡,增添了一種擁有如此執著而深刻的視點,體會一種實現影像經典與堅持走在自己道路的攝影人生。在現代攝影手法與風格百花齊放的創作裡,他的影像依舊蘊涵著深厚雋永的人文風格,彷彿時光凝結在過往,也投射穿越至現代,細細低迴於其中,令人回味無窮。

——

注1 吳嘉寶(1993)〈台灣攝影簡史〉視丘文化評論。

注2 2022年8月31日,筆者於葉裁北埔住處進行訪問時的談話內容。

原文出處|

非池中藝術

刊登網址: https://artemperor.tw/focus/5505

刊登日期:2023年6月30日

A Seeker Steadfast on the Path of Photography

Peng-Hui Hou|D.Art from Nihon University Graduate School of Art

Born in the Bajian Hakka settlement in the Erhlin Township of Changhua County in 1946, Cai Ye has enjoyed a unique life history and photographic career. As a photographer, he has taken many treasured documentary images of Taiwan’s countryside.

Inspiring First Encounter with Photography: Sang-Hsi Cheng

In his early encounters with photography, the young Cai Ye was introduced to Taiwanese photographer Sang-Hsi Cheng, who remained a memorable inspiration and source of encouragement throughout his life. In addition to the professional guidance and mentoring on aspects of photography from Mr. Cheng, Cai Ye also read many professional books on photography at his instructor’s home, which greatly expanded Cai Ye’s imagination on the artistic expression of photography.

Jia-Bao Wu, a researcher on Taiwan’s photographic education, once located Sang-Hsi Cheng within Taiwan’s photographic history as a photographer who bridged the first generation (those who studied photography in Japan or China, including Tsai Chang, Ming-Tiao Lee, Nan-Guang Deng, etc.) and the second generation (represented by the Visual-10 Group of the 1970s) of Taiwanese photographers. (Note 1).

Compared with the previous generation, who moved toward aesthetically-pleasing compositions and painterly settings in photographic salons, the style of Sang-Hsi Cheng’s images retained a documentary tone while emphasizing the relationship of visual resonance between different elements within the image. Sang-Hsi Cheng eschewed the deliberate aesthetics of mainstream salon photography and tended instead toward capturing and documenting natural expressions and conditions in people’s lives as his photographic emphasis. Cai Ye’s prolific cultural and landscape photographs taken in the Hsinchu region from the 1960s to the 1970s reveal the profound influence of Cheng’s photographic concepts on his work during that period.

Not only did Sang-Hsi Cheng’s knowledge of photography inform his own creative expression, he also actively mentored many emerging photographers. He played a pivotal role in the development of Taiwanese photography of that era. Cai Ye’s opportunity to study with Mr. Cheng during this period established an important foundation for the direction of his future path in photography.

The Experience and Impact of International Photographic Work Exchange

In 1975, Cai Ye became a contract photographer for the Eastman Kodak Company the follow year, responsible for photographing countries with historical sites over a century old. During this period, Cai Ye gained practical experiences in photography, and observed firsthand the diverse urban and cultural vistas in different countries.

Furthermore, during his time working abroad, Cai Ye participated in workshops lead by world-renowned photographers, including Ansel Adams (1090-1984), the famed black-and-white photographer who developed the zone system; and Shinzo Maeda (1922-1998), most notable for his landscape photographs of Biei and Furano in Hokkaido; as well as Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) whose book “The Decisive Moment” changed the course of photography on a global scale. In terms of both technical expertise and photographic perspectives, Cai Ye’s invaluable experiences of exchange with these renowned photographers (Note 2) was unique and rare among his contemporaries in Taiwan’s photography circles.

The wealth of cumulative experiences during this period reenforced Cai Ye’s unwavering steps on the path of photography. From his professional commitment to personally entering the darkroom to produce the details in his black-and-white photographs, to his pursuit of rich and detailed views of landscapes through extended intensive shooting at a designated location, as well as in his emphasis on visual elements achieving mutual harmony and order in his street photography – each bear similarities with the photographers mentioned above. However, Cai Ye has further amalgamated these characteristics to create a unique photography style of his own.

Upon leaving the Eastman Kodak Company in 1984, Cai Ye returned to Taiwan and settled in Emei, Hsinchu after getting married. Though Taiwanese photography during this period underwent a movement toward reportage photography with a local emphasis, Cai Ye was not influenced by these external trends in photography, but instead returned to his original intentions. He continued to persist in his own photography path by further delving into capturing images of the countryside of Taoyuan, Hsinchu, and Miaoli. His years of experience in photography set him apart from other photographers in both the quality and quantity of his images. In the developmental history of Taiwanese photography, there remain images that await further exploration or possible interpretation through a contemporary perspective, which impart a particular significance to the publication of this book.

Photographic works that require frequent movement over extended periods of time often present a higher degree of difficulty than that of photographers who work in their own locality or hometowns. Cai Ye’s long-term photographic focus on the pastoral panoramas surrounding Beipu perhaps initially began from his childhood memories, then shifted to long-term photography after he moved away, and gradually transformed into a self-regard and irreplaceable image reality experiment that could not be easily achieved with an ordinary level of motivation or mere resolve.

Furthermore, Cai Ye has continued to produce his photographs in a self-built darkroom in his home. In that 8 to 10 square meters of space, there are self-modified enlargers; a long, narrow work bench on which developing trays fit perfectly; and a small bed and canvas wardrobe – these form an integrated space of darkroom-cum-minimalist bedroom. The average photographer will have a difficult time imagining a lifetime of darkroom work in such a darkroom. Even in such an extreme environment, Cai Ye’s state of mind remains free and unfettered in his lifelong practice, with photography as his companion.

A Photographic Arrangement of Visualized Images

Cai Ye’s style of snapshot-based photography creates images rich with story. A single photograph yields a wealth of interpretable content. The images reveal a robust sense of rural life within the ordinary, and without exaggerated perspectives. There is a balance between the country vistas, festival rites, human figures, events and objects, in the capture of images that also embody characteristics unique to the Hakka communities of Hsinchu and Beipu. Rather than editorialize as a chronical or catalogue, this book of photography can be regarded as an independent work that construct a visual narrative of the larger era by organizing the numerous images through contemporary editorial methods.

The images collected in this photo anthology include Cai Ye’s work before his stint abroad (including some photographs shot in Taiwan on temporary visits home), and after his return, each comprising approximately half of the contents. Among these, 40 percent are images from the 1960s and 1970s, giving the book a nostalgic tone. Broadly viewed, there is a sense of temporal flow in the book; while on closer inspection, the arrangement is not strictly chronological; rather, there is an emphasis on the contextual relationship of the visual images that enable an experience of an integrated whole. This is the unique presentation of historical images as realized by this book.

From misty mountain landscapes, to forays into hillside towns -- views of the simple rural life is revealed in the moments of diligent harvest as well as in moments of respite and conversation. These are interspersed with unique local scenes and bygone customs such as pit kilns, stage performances, and roadside stalls; or with religious events such as qianggu (grappling with ghosts), the King’s Boat Burning Festival, and Mazu; as well as with scenes from annual indigenous celebrations. The wealth of images interface with scenes from the lives of Taiwan’s various ethnicities. There are also images of transportation arteries that connect with points afar, such as pontoon bridges, and railroads. The panoramic shots capture the trajectories of people living in these environments; when alternated with closeups of people, objects, and landscapes, a meandering sense of flowing time is constructed. The occasional travel through time and space, with jump cuts to the expressions of children playing beneath an openair stage, seems to connect the cumulative mood and atmosphere of the past and present.

The imagery of water is an important visual among the images that interweave various categories, times, and spaces. In addition to rivers, streams, and costal landscapes, there are also photographs of laundry ditches, shrimp fishing, drift wood, and figures on the embankment – fully expressing the lives of people who live alongside bodies of water. The final image in the book depicts Emei Creek, with the broad expanse of the river channel in the foreground extending toward the view of distant mountains. The grandeur that also retains detailed expression allows the rich imagery of pulsing waters to converge through to the very last, condensing and coalescing as they flow toward the distance.

Luminous Landscapes continues to delve deep into the images of the countryside, while repeatedly pivoting between eras. Traditional images are transformed through contemporary editorial methodology and imbued with a renewed possibility of learning about and experiencing the charms of Cai Ye’s images.

Cai Ye has always focused on the pursuit of his own creative world. The temporal span of his extended photographic studies, and the transitions in the conditions in the lives of the community that they reveal, are all preserved within his photographic works. They are meaningful both as expressions of personal artistic practice and as records of the history of Taiwan’s development.

Cai Ye’s images have added a persistent and profound perspective to the development of photography in Taiwan, as well as the experience of a life of photography that actualizes the classical in images and insists on a path of one’s own. Among the plethora of photographic techniques and proliferation of creative works today, his images continue to embody a profound and enduring refined style, as though a moment crystalized in the past that refracts into the present, where it lingers in fine strands, endlessly evocative.

——

Note 1: Jia-Bao Wu (1993), “A Brief History of Taiwanese Photography,” Fotosoft Cultural Review.

Note 2: As discussed during an interview conducted with Cai Ye at his residence in Beipu on August 31, 2022.